You are going home this night to your home of winter,

To your home of autumn, of spring, and of summer;

You are going home this night to your perpetual home,

To your eternal bed, to your eternal slumber.

- The Carmina Gadelica

Roots, memory, heritage. It’s all there in consciousness, the wherewithal to encounter who we were, once. The antiquity of lineage, the long spiral of time and recall that defines each of us.

Memoir itself is an evocative thing, the chance to intuit the past through someone else’s eyes.

And there are so many worlds to experience through the genre of memory. Some seem strange and foreign; others familiar and close.

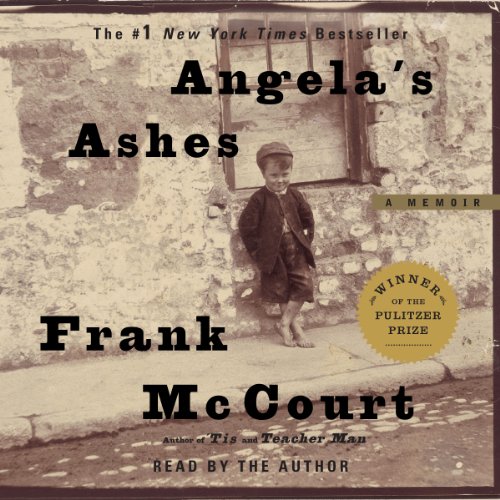

It’s why I am drawn to Angela’s Ashes, Frank McCourt’s 1996 Pulitzer Prize winning memoir. His story lives in my blood; like exile – the rich and evocative account of the author’s young life, the telling of his Irish immigrant parents, their meeting in Brooklyn, New York, and subsequent marriage in March, five months before Frank’s birth. It’s all a proxy meeting with my own lineage, with the past, both ancient and close.

McCourt begins his own story as a three-year old on a playground in Brooklyn. He is with his two-year old brother, Malachy, on a seesaw, when Malachy falls off. Their mother, Angela, takes Malachy to the hospital, where, she says, he receives “stitches galore” because he “nearly bit off his tongue.”

McCourt’s memoir continues in the voice of a young child, and grows as he does, reflecting on his life as a young adolescent, and finally, as a nineteen-year old teenager. Each period of Frank (Frankie) McCourt’s life is marked by extreme poverty. The McCourt family returns to Ireland, to Limerick, when Frankie is four, in hopes of a better life, but that hope is never realized. McCourt’s ne’er do well father, Malachy, is a perpetual drunk who doesn’t stay on a job for more than a few days. Despite this, the author conveys a deep sense of attachment to his father and to his immediate and extended family by crafting and recreating the language of his childhood, words that evoke visceral memory; sayings that are connected to the sentiment of a people. Malachy’s refrain, Och, aye, is heard throughout the book, a small habit of speech that is both endearing and reminiscent of the Irish tongue. McCourt draws language around each scene in such a compelling and tenderhearted way that every character is a unique silhouette, a beautiful space on the page.

Part of my own lineage begins in Ireland. My father’s grandparents fled to New York from Limerick during the Great Famine. It was a land that I envisioned for a long time. A land that’s sod was turned and formed by hands of ancestors. Part heartache and part legacy, a place that I could see and hear from a long way off.

As I read McCourt’s memoir, that land, that space of ancestors, of dust and ash, moved further into my line of sight. And the blurred lines of grief, etching through time, caught me, here in my own time.

And I was compelled to believe in, to trace those filaments of grief, again, when I read McCourt’s account of his young brother, Eugene, his small death; how his Uncle Pa Keating, volunteers to place the child’s body in the coffin:

“I’ll put the child in the coffin, he says. He limps to the bed and places his arms around Mam’s shoulders. She looks up at him and her face is drenched. He says,

“I’ll put the child in the coffin, Angela.”

“Oh, Pat, she says, Pat.”

“I can do it, he says. Sure, he’s only a small child an’ I never lifted a small child before in my life. I never had a small child in me arms. I won’t drop him, Angela. I won’t. Honest to God, I won’t.”

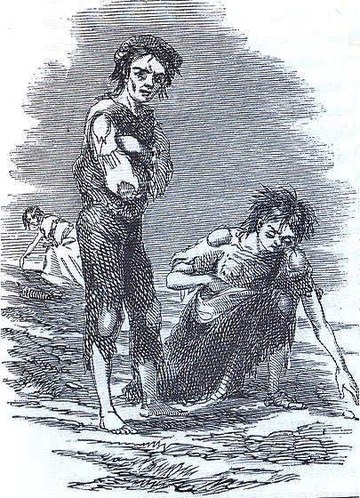

The pull of grief, of separation and rupture is imbedded in Irish culture, in the history of Celtic lore. The loss is felt in the deaths of at least one million people between 1846 and 1851. Starvation and diseases related to malnutrition took so many, their corpses left on roads and ditches, their eyes dead long before their last breath was taken.

And it’s not just physical death that is mourned, but the partitioning of living souls, the loss of loved ones through emigration.

In 1847 alone, a quarter million Irish left home for the shores of America and other foreign lands. Over the course of the famine, two million people were believed to have emigrated. So many were young, just beyond the demarcation of childhood, eighteen, nineteen years old. As the day of the departure loomed, the family of the soon departed began a sort of mourning, for they knew that they would not see their son or daughter again. A wake of sorts was planned for the last night. It was a tradition that harkened back to to Ireland’s pagan ritual of “waking” the dead, wherein loved ones gathered to watch over the dead person’s corpse during the night before burial in an effort to prevent evil spirits from entering the body.

And now, on the night of the wake, family and friends were left to mourn their living child, a child they knew would survive, in the flesh, a child they knew they would be forever parted from on this earth.

Throughout his memoir, McCourt evinces the depth of attachment not only to family, but to his native Ireland, the culture that he grew from. The reader senses a bond between the author and his environment, his schooling, his family, and especially his father, who imprinted a deep sense of Irish history into young Frankie McCourt’s soul. Malachy’s frequent references to Cuchalain, the Irish demi-god, his little speeches about how “we all have to die for Ireland,” his drunken singing of patriotic anthems – each of these told and retold with much hilarity and a certain amount of reverence by the author – show an attachment between father and son. The attachment to culture is intertwined with the father’s spirit, a spirit that floats through the entirety of the memoir.

The language of culture is heard through other voices as well, from the school masters to the nurses and nuns at the Fever Hospital where Frankie was a typhoid patient when he was nine years old. The nurse on that ward, in fact tells Seamus, the janitor, that:

This was the fever ward during the Great Famine long ago and only God knows how many died here, brought in too late for anything but a wash before they were buried and there were other stories of cries and moans in the far reaches of the night.

The poignant history of Ireland repeats again and again through the characters’ speech and voices. The Famine, the 800 years of British rule, the profound impact of the Catholic Church on the Irish people – all of this is reflected in McCourt’s memoir. And the author’s life is played out with great humor and deep sadness, a simultaneous casting of faith and despair. Reflecting on his upcoming Confirmation preparation, McCourt states, “I want to tell them I won’t be able to die for the Faith because I’m already booked to die for Ireland.”

And I will always be taken with what was, the rawness of memory, an entangled spirit that moves toward us in time. The way my mother said that the map of Ireland was written all over my father’s face. We must not live in the past, but the past always lives in us is what I think she meant by that.

And I will see my father’s hands again and again, gathering; opening, knots of flesh, moving earth; tendering dust.

McCourt’s memoir speaks to the persistence of memory, and its placement in the fabric of culture and identity. His writing is reminiscent of our bonding to culture; a reminder that language evokes and transcends individual imagery of the past, and like each of us, persists, to recreate memory; to live again.

Heffernan Research offers a range of English language tutoring options. Individual and small group sessions are available. Special classes on focused topics, such as essay writing, are also offered throughout the year. Margot works with ESL students as well as individuals who need to enhance specific English language skills.

Heffernan Research offers a range of English language tutoring options. Individual and small group sessions are available. Special classes on focused topics, such as essay writing, are also offered throughout the year. Margot works with ESL students as well as individuals who need to enhance specific English language skills.

Margot Heffernan has solid and extensive experience writing about a broad range of medical topics. She uses her expertise to provide comprehensive and academically sound papers for medical malpractice, product liability, and personal injury lawyers as well as other professionals who need reliable medical information.

Margot Heffernan has solid and extensive experience writing about a broad range of medical topics. She uses her expertise to provide comprehensive and academically sound papers for medical malpractice, product liability, and personal injury lawyers as well as other professionals who need reliable medical information.